TLDR

The capacity of a lead acid battery isn’t what it appears and varies depending on the amount of current being drawn from it. This makes calculating the runtime for any given current and battery capacity a tad challenging. There is a rule that applies to get round this – Peukerts.

7Ah – 7 Amps for 1 hour?

You might think that a 7Ah (Amp hour) battery will provide 7 Amps for 1 hour as this is inherently logical. However, lead acid batteries are a bit strange. The more current you take from them, the less capacity they actually have.

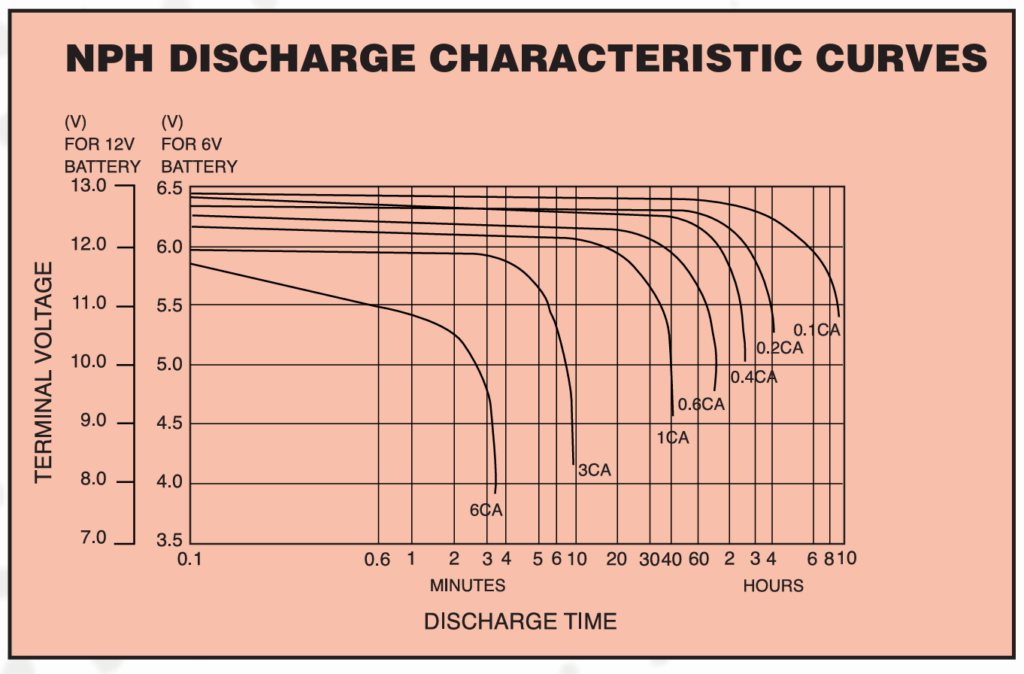

Take a look at the chart above taken from the Yuasa NPH range of batteries. You can see that at 1CA (1 x the capacity, so for a 7Ah block this would be 7A), the amount of time it will provide power for is in fact 40 minutes and not 1 hour.

So why 7Ah?

The actual capacity is specified as a 20 hour rate (C20). So a 7Ah battery will provide 7/20A => 0.35A => 350mA for 20 hours. Note that some larger batteries may be specified at a 10 hour rate (C10). For example a 100Ah C10 battery will provide 10Amps for 10 hours. Since the less current you take the more capacity you have, discharging this battery at C/20 will yield a higher than expected rating. So basically a battery rated at 100Ah at C10 has higher capacity than one rated at C20.

Peukert’s Formula

C_{actual} = C_H \cdot \Bigg( \frac {C_H / H} I \Bigg) ^ {k-1}\begin{gather}C_{actual}= \text{The Capacity at this discharge} \\H = \text{ Rated discharge time in hours} \\C_H = \text{Rated Capacity} \\ I = \text{Actual constant current draw} \\ k= \text{The Peukert exponent} \end{gather}WTF was that?

When we think about it, the standard discharge formula would be relatively easy.

\text{Time (hrs)}=\frac {\text{Battery Capacity (Ah)}}{\text{Current Draw (A)}}But since the more current you draw, the less capacity the battery has, Peukert’s formula adjusts for that. Now you can calculate the Peukert exponent from a set of data points according to this formula:

k=\frac {\log(T_2)-\log(T_1)} {\log(I_1) - \log(I_2)}However, taking two random datapoints gives different answers because the Peukert exponent is an approximation for what is a complex chemical reaction. So the generally accepted value to use is 1.25. But if you want to calculate your own – here’s our Peukert Calculator.

Example

We want to calculate runtime. So let us assume we have an AC load of 648W, powered by a UPS with a DC to AC efficiency of 90%. This means the power given up by the battery is:

P_{batt} = \frac {648} {0.9} = 720 \text { Watts}And let us assume the UPS has a battery pack comprising of 3 blocks of 12V 9Ah. So the voltage of the battery string is 3×12=36V and therefore the current delivered by each block is:

\frac {720} {36} = 20 \text { Amps}Based on the formula:

\text {Current} = \frac {Power} {Voltage}Without Peukert we would calculate based on Time = Battery Capacity over Current that the answer would be:

Time = \frac 9 {20} = 0.45 hrs => 27 minsBut going back to Peukert, the actual capacity is a tad less:

C_{actual} = C_H \cdot \Bigg( \frac {C_H / H} I \Bigg) ^ {k-1}H is 20, CH is 9, k=1.25 and I is 20:

C_{actual} = 9 \cdot \Bigg(\frac {9/20} {20}\Bigg)^{0.25}And this works out at very close to 3.5Ah.

So going back to this formula:

\text{Time (hrs)}=\frac {\text{Battery Capacity (Ah)}}{\text{Current Draw (A)}}Then

\text {Time} = \frac {3.5} {20} = 0.175 \text {hrs} => \text {10.5 minutes}

A lot less than the 27 minutes if everything would’ve been ideal.

Other Factors

Now so far we have only considered the efficiency of the inverter, e.g. how well it can convert DC from the battery into AC. However there are other losses that need to be considered, especially at low power draws. The electronics in the UPS will consume some power, regardless of the load and this needs to be accounted for, however, in the scheme of things, these can be disregarded unless we are dealing with very low loads – in which case the result is altogether fraught with inaccuracies.

I want to calculate the battery capacity for a particular load and runtime

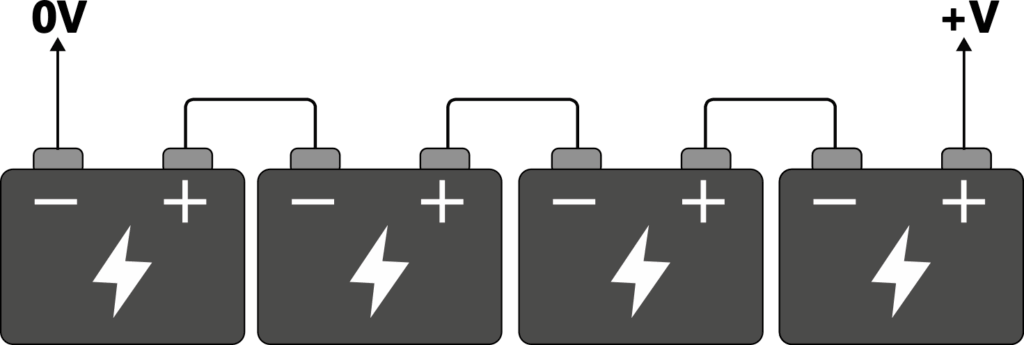

You can do this! You need to define the battery string voltage and the number of strings. If you’re not familiar with what this is, let me give you an example.

There are 4 battery blocks here with the positive of the first, connected to the negative of the next and so on. This is a single battery string. If each battery block is 12V and a capacity of 9Ah, then the voltage between +V and 0V would be 48V, but the capacity would remain the same at 9Ah. The amount of blocks can be any number and every time you add a block the voltage increases and the capacity remains the same. You must always use the same type of block in a battery string.

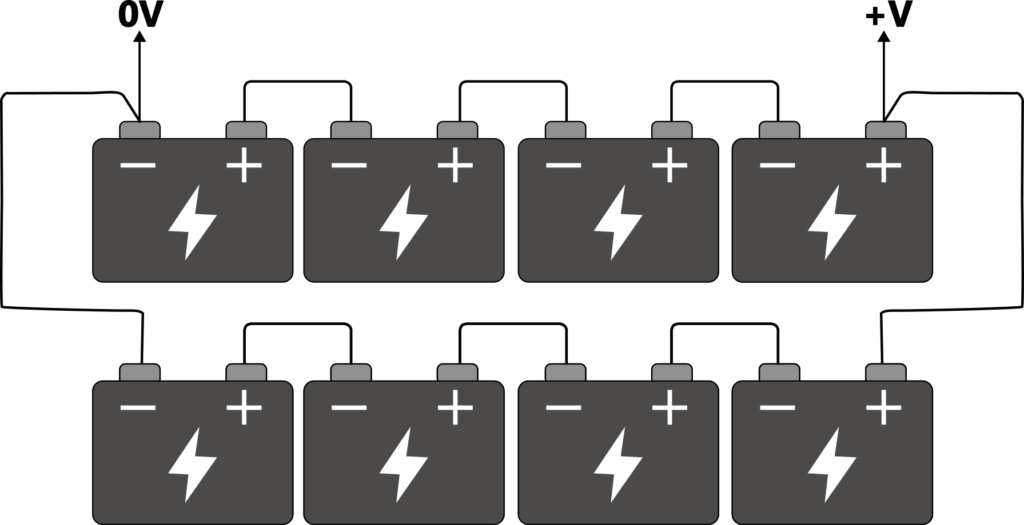

Now if we add another identical string and connect the first negatives and last positives, now we have a system with 2 strings. The voltage at +V has not changed (e.g. in this case it is still 48V), but the capacity has now doubled (e.g. 18Ah). In order to communicate the makeup of the string we could refer to it as a 4S2P string, 4 in series, 2 in parallel. We can keep going in order to increase capacity to meet requirements.

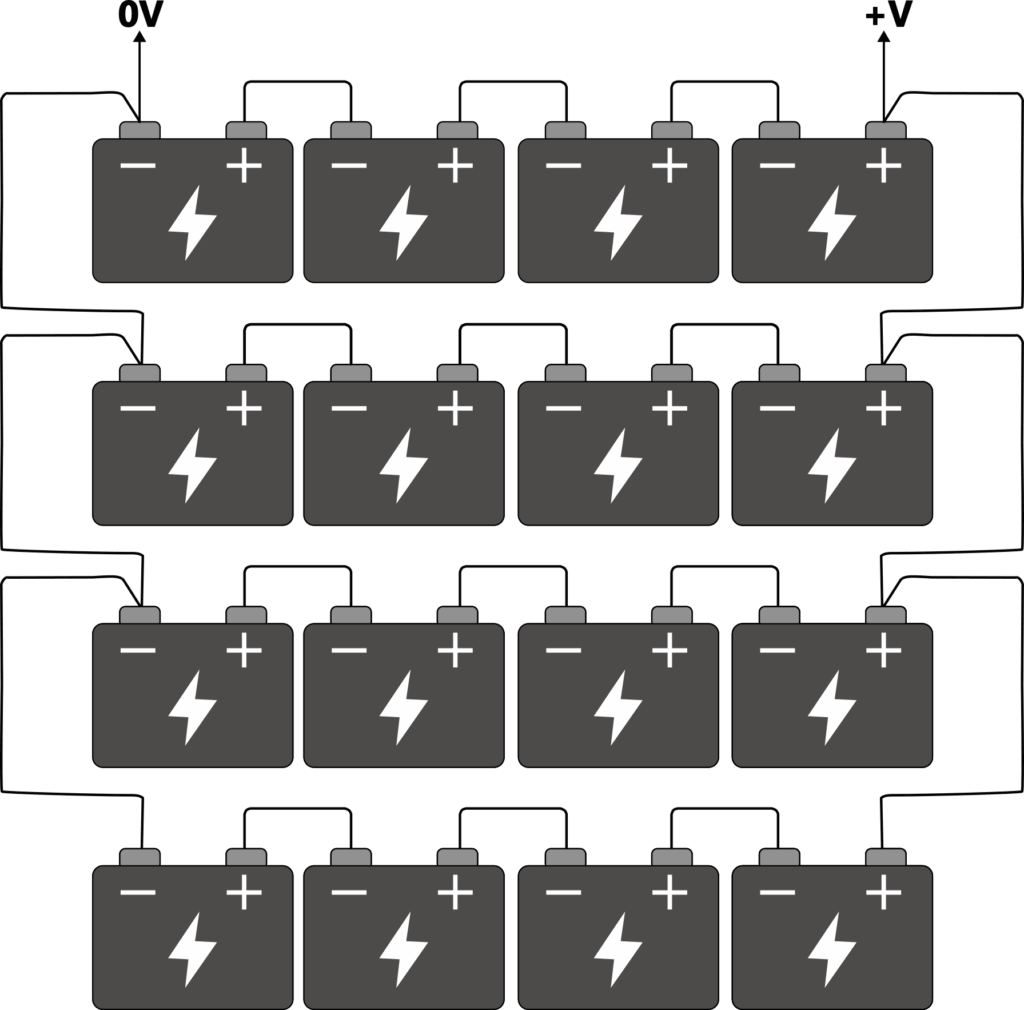

So here, in this 4S4P arrangement we have a string voltage of 48V and a capacity of 36Ah. It’s important to understand this as it is better to have as few strings as possible, but this cannot be helped sometimes. For example you may only have battery packs that are rated at 9Ah and if you needed 36Ah then you would need four of them. However, if you had a bespoke cabinet you could use a single string of batteries greater than or equal to 36Ah.

Got that – what next.

We need to calculate the rated capacity – CH. To do this we need to know how much current is being drawn out of every battery.

I= \frac P {N_S \cdot V_S}\text Where: \\ \begin{gather} I = String Current \\ P = Power Required \\ N_S = Number of Strings \\ V_S = String Voltage \end{gather}Now go back to the Peukert equation above

C_{actual} = C_H \cdot \Bigg( \frac {C_H / H} I \Bigg) ^ {k-1}And rearrange this for CH . This needs some good Maths or chatGPT skills so here’s the formula:

C_H = \Bigg \lbrack C_{ACT} \cdot \big(H \cdot I \big)^{k-1} \Bigg \rbrack ^{1/k}And there you have it. A bit of a calculator dreamland but it has all done in the UPS Calculator for you!